Kannon : The Japanese Bodhisattva of Compassion and Mercy

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Japanese Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | N/A |

| Region | Japan |

| Associated With | Compassion, Mercy, Protection, Healing, |

Kannon

Introduction

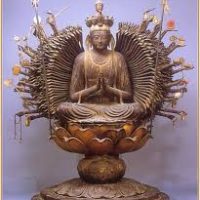

Kannon is among the most widely venerated figures in Japanese Buddhism, revered as the embodiment of compassion and mercy. Known formally as a bodhisattva rather than a deity, Kannon represents the Japanese manifestation of Avalokiteshvara, whose origins lie in Indian Mahayana Buddhism. The name Avalokiteshvara translates to “the one who perceives the cries of the world,” a concept that defines Kannon’s spiritual role across centuries of belief and practice. Buddhism reached Japan in the sixth century through the Korean Peninsula, and with it came the cult of Kannon, which quickly took root among both the elite and common people. Over time, she evolved into a deeply personal figure of solace, approached not only for enlightenment but also for protection, healing, and everyday guidance. Unlike more distant cosmic Buddhas, Kannon became approachable, present, and emotionally resonant, often invoked in moments of fear, grief, or uncertainty. This closeness to human suffering explains why Kannon remains one of the most enduring spiritual figures in Japan even today.

Physical Traits

Kannon’s physical appearance is intentionally fluid, reflecting the bodhisattva’s ability to adapt to the needs of suffering beings. In early Indian representations, Avalokiteshvara appeared male, but in Japan Kannon gradually assumed a feminine or androgynous form, emphasizing maternal compassion rather than authority. Most depictions present her with a calm expression, half-closed eyes, and elongated earlobes, symbolizing wisdom and attentiveness. Flowing robes, lotus flowers, and a serene posture convey spiritual purity and inner stillness. Some forms display multiple heads or arms, not as literal anatomy but as symbolic extensions of awareness and action. The Eleven-Headed Kannon reflects the capacity to observe suffering in every direction, while the Thousand-Armed Kannon represents limitless assistance offered simultaneously to countless beings. Other manifestations, such as the Horse-Headed Kannon, appear more forceful, illustrating compassion expressed through protection and decisive intervention. Across all forms, the defining trait remains the same: a visual language of mercy, responsiveness, and quiet strength.

Family

Kannon does not possess a biological family in the mythological sense, as bodhisattvas exist outside human lineage. Instead, Kannon’s relationships are defined spiritually within Buddhist cosmology. Most notably, Kannon is closely associated with Amida Buddha, the Buddha of Infinite Light who presides over the Western Pure Land. In Pure Land traditions, Kannon serves as an attendant to Amida, guiding souls toward rebirth in that realm of liberation. This relationship is often depicted in temple art, with Kannon standing beside Amida as an intermediary between the enlightened and the suffering. Another important association is with Seishi Bosatsu, who represents wisdom and spiritual power. Together, Amida, Kannon, and Seishi form a sacred triad that emphasizes compassion balanced with insight. Rather than lineage, these relationships express function and purpose, positioning Kannon as the compassionate force that bridges divine enlightenment and human vulnerability.

Other names

Kannon is known by several names, each highlighting a different dimension of the bodhisattva’s nature. The most direct Japanese rendering of Avalokiteshvara is Kanzeon or Kanjizai, both referring to the act of perceiving the sounds or cries of the world. The honorific Kannon Bosatsu is commonly used in devotional contexts, reinforcing her status as a compassionate guide rather than a creator god. In older English texts, the spelling Kwannon occasionally appears, reflecting early attempts to transliterate Japanese pronunciation. Beyond Japan, Kannon is closely related to Guanyin in China, Gwaneum in Korea, and Quan Âm in Vietnam, all culturally distinct yet spiritually aligned manifestations of the same compassionate principle. These names reveal how the figure transcended geography while retaining a consistent core identity rooted in mercy and attentive listening.

Powers and Abilities

Kannon’s powers are defined not by domination or punishment but by the alleviation of suffering. Central to these abilities is the capacity to hear prayers from anywhere, regardless of distance or circumstance. This omnipresent awareness allows her to respond swiftly to those in distress. Another defining power is the ability to manifest in multiple forms, traditionally described as thirty-three distinct appearances, each tailored to guide different beings toward liberation. These manifestations may appear as monks, women, warriors, children, or even non-human figures, depending on what will best reach the individual. Kannon is also widely invoked for protection from natural disasters, illness, travel dangers, and childbirth complications, making the bodhisattva especially significant in everyday devotional life. In Pure Land belief, Kannon plays a vital role in escorting souls after death, offering reassurance at the moment of transition. These abilities reinforce Kannon’s reputation as an ever-present guardian whose compassion operates actively within the world.

Modern Day Influence

Kannon’s relevance has not diminished in the modern era. Across Japan, temples dedicated to Kannon continue to attract pilgrims, tourists, and worshippers seeking comfort or clarity. Pilgrimage routes such as the Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage remain active spiritual journeys that blend tradition with personal reflection. In contemporary art and literature, Kannon frequently appears as a symbol of empathy, moral responsibility, and quiet resistance against cruelty. The bodhisattva’s imagery has also influenced modern popular culture, from manga and anime to symbolic references in film and fashion. Even outside explicitly religious contexts, Kannon’s association with compassion subtly informs social values around care, patience, and communal responsibility. Internationally, Kannon’s connection to Guanyin has helped establish the figure as one of the most recognizable icons of Buddhist compassion worldwide. This enduring presence demonstrates how Kannon continues to evolve while remaining rooted in timeless ideals.

Related Images

Source

Fowler, S. (2016). Accounts and images of Six Kannon in Japan. University of Hawai’i Press. https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/accounts-and-images-of-six-kannon-in-japan/

Japan Experience. (2024). Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy in Japanese Buddhism. https://www.japan-experience.com/plan-your-trip/to-know/understanding-japan/kannon

Kitazawa, N. (n.d.). Me no shinden (Temple of the Eye). (Referenced in modern Japanese art history).

Onmark Productions. (2012). Kannon Bodhisattva (Bosatsu) – Goddess of Mercy. https://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/kannon.shtml

Onmark Productions. (2008). The Many Forms and Functions of Kannon in Japanese Religion and Culture. https://www.onmarkproductions.com/Many_Forms_and_Functions_of_Kannon_in_Japanese_Religion_and_Culture.htm

Sakamoto, T. (2005). Handbook of Japanese mythology. World Religions Library. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/handbook-of-japanese-mythology-2/

Wikipedia. (2024). Guanyin. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guanyin

Faure, B. (1998). The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender. Princeton University Press.

Covell, S. G. (2005). Japanese Temple Buddhism: Worldliness in a Religion of Renunciation. University of Hawaii Press.

Reader, I. (1991). Religion in Contemporary Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

Sharf, R. H. (1999). On the Allure of Buddhist Relics. Representations, 66, 75–99.

Lopez, D. S. (2002). A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West. Beacon Press.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Kannon a god or a bodhisattva?

Kannon is a bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism, not a creator god, dedicated to alleviating suffering and guiding beings toward enlightenment.

Is Kannon the same as Guanyin?

Yes, Kannon is the Japanese manifestation of Avalokiteshvara, known as Guanyin in China and Gwaneum in Korea.

Why is Kannon often depicted as female in Japan?

While originally male in Indian tradition, Kannon evolved into a feminine form in Japan to emphasize maternal compassion and mercy.

What do people pray to Kannon for?

Devotees pray to Kannon for protection, healing, safe childbirth, guidance, and relief from emotional or physical suffering.

What are the different forms of Kannon?

Common forms include Eleven-Headed Kannon, Thousand-Armed Kannon, Horse-Headed Kannon, and Holy Kannon, each symbolizing a specific aspect of compassion.