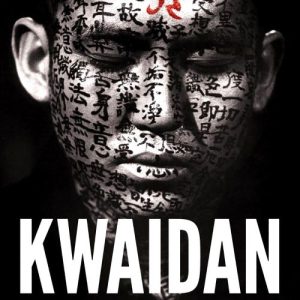

Kwaidan (1964)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Genre | Horror |

| Cast | Tatsuya Nakadai, Rentarō Mikuni, Tetsurō Tamba, Keiko Kishi, Michiyo Aratama |

| Directed by | Masaki Kobayashi |

Masaki Kobayashi’s 1964 masterpiece Kwaidan stands as one of the most evocative cinematic explorations of Japanese mythology ever made. Adapted from Lafcadio Hearn’s collection of Japanese ghost stories, the film transforms age-old folktales into haunting visual poetry. With its painterly cinematography, slow, meditative pacing, and reverence for traditional legends, Kwaidan is less a horror film and more a mythological tapestry woven with the threads of Japan’s spiritual heritage.

The title Kwaidan, meaning “ghost story,” immediately signals its connection to kaidan-shu, a Japanese term for supernatural tales rooted in Buddhist and Shinto beliefs. The film’s four stories—The Black Hair, The Woman of the Snow, Hoichi the Earless, and In a Cup of Tea—each draw deeply from myth and folklore, exploring how the supernatural world interacts with human desires, guilt, and fate. Kobayashi’s approach is reverential; he treats mythology not as superstition, but as a living philosophy that reflects Japan’s relationship with nature, mortality, and the unseen.

In The Black Hair, the story of a samurai who abandons his loving wife for wealth echoes the Buddhist themes of karma and the eternal consequences of one’s actions. When the samurai returns to his old home, he finds time itself distorted—a mythological motif symbolizing how greed and betrayal disrupt the natural order. The ghostly hair that entangles him is both literal and symbolic, embodying the inescapable grip of guilt. Through this mythic retribution, Kobayashi reminds viewers of the moral core that underlies much of Japanese mythology: harmony must never be broken without consequence.

Perhaps the most ethereal segment, The Woman of the Snow, is drawn from the legend of Yuki-onna, the snow spirit who appears to travelers lost in blizzards. Kobayashi’s depiction of this icy goddess captures both her beauty and her danger, embodying the dual nature of the natural world—nurturing yet merciless. The blue-tinted visuals and silent snowfall give the segment an otherworldly atmosphere, making Yuki-onna feel less like a ghost and more like a living embodiment of nature’s will. Her warning to her human lover not to reveal her existence mirrors the Shinto belief in maintaining balance and secrecy between the human and spirit realms.

Hoichi the Earless stands as the film’s most explicitly mythological tale, recounting the tragic story of a blind musician who performs the Heike Monogatari for the restless spirits of fallen samurai. This story bridges history and legend, bringing to life the Buddhist concept of attachment and the restless suffering of souls who cannot move on. The priests’ act of inscribing sutras on Hoichi’s body to protect him from spirits is a powerful visual symbol of faith as armor—a motif deeply rooted in Buddhist myth. Kobayashi transforms this tale into a grand opera of the afterlife, with ghostly armies, ritual chants, and the haunting sound of the biwa echoing through the darkness.

The final story, In a Cup of Tea, draws on the age-old idea that spirits can inhabit objects, a belief common in Shinto cosmology where every object or natural element possesses kami, or spirit. The protagonist’s reflection in the tea becomes a portal to the supernatural, blurring the boundary between perception and possession. This subtle horror speaks to the mythological idea that the spiritual world is not distant but ever-present, sometimes revealed in the most ordinary moments.

Beyond its narratives, Kwaidan is mythological in its very construction. The film’s deliberate artificiality—the painted skies, stylized sets, and minimal dialogue—creates an atmosphere closer to Noh and Kabuki theatre than modern cinema. These artistic choices evoke ancient performance traditions where myth was not merely told but ritually reenacted. Every frame of Kwaidan feels like a shrine to Japanese storytelling, capturing the serenity, melancholy, and spiritual ambiguity that define the country’s folklore.

Kobayashi’s direction emphasizes stillness and silence, allowing the myths to breathe. There are long pauses where the camera lingers on faces, landscapes, and colors—inviting the viewer to meditate rather than simply watch. In doing so, Kwaidan mirrors the meditative nature of Buddhist art, where emptiness and quiet carry as much meaning as action or dialogue. The film’s hypnotic pacing and painterly composition turn myth into a living aesthetic experience, transforming the screen into a sacred space.

What makes Kwaidan remarkable is how it transcends the label of “ghost story” to become a profound reflection on mortality and moral consequence. It does not seek to frighten but to awaken—a trait shared by much of traditional Japanese mythology, where the supernatural is a moral force rather than a monstrous one. The spirits in Kwaidan are not villains; they are cosmic agents of balance, reminding humans of their place in a greater spiritual order.

Six decades after its release, Kwaidan remains a cinematic monument to the power of myth. It bridges the old and the modern, the living and the dead, through a visual language that honors Japan’s ancient traditions while achieving timeless artistic beauty. For those fascinated by mythology, folklore, and spiritual storytelling, Kwaidan is not merely a film—it is a sacred encounter with the essence of Japanese belief and the haunting poetry of its ghosts.